Cross-Country Road Trips

Pre-freeway, pre-seatbelt odysseys from D.C. to Mesa, powered by baloney sandwiches, breakdown detours, and endless questions whispered into Dad's ear.

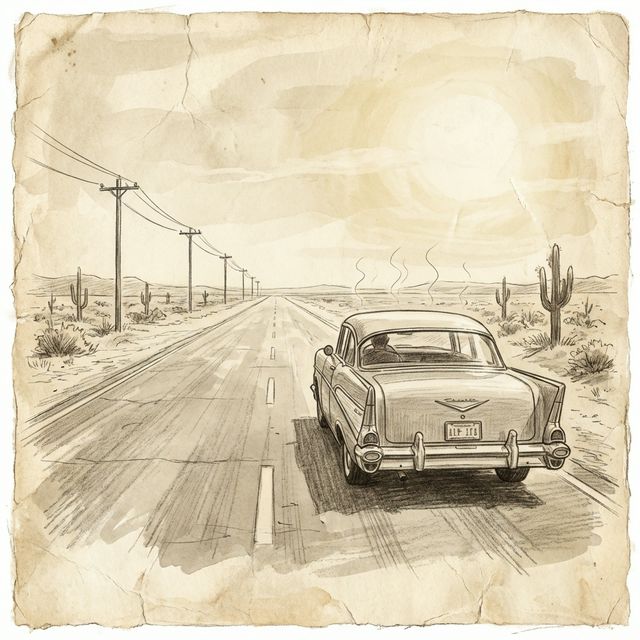

Every summer during the medical school years, the family would pack up and drive from Washington, D.C., to Mesa, Arizona, as soon as school let out, then rush back in the fall. This was the late 1940s and early 1950s, before the Interstate Highway System existed, and the trips were marathons of endurance on narrow two-lane roads.

Great-Grandpa Clifford "had to cross the country in four or five days," and conditions were spartan. Dad remembered being "loaded, half asleep, at 0400 into the car and then, asleep again, being lugged into an inexpensive motel room at 2200". Mom later told him that they rarely even sprang for a motel: "most of the time we did not even stay in a motel, but slept in the car in the garage that was going to repair the car the next morning when it opened".

The old black car broke down frequently, and Dad had vivid memories of his father "trying to wake up a gas station owner so we could travel through the night (many operators lived in apartments above the station), and finally giving up. We had to sleep in the empty lot of the station". Meals were equally no-frills: "Most of the stops were to relieve ourselves behind bushes at the side of the road and most of the meals were baloney or cheese sandwiches, always on white bread with mayonnaise, eaten with Kool-Aid while we were driving".

Dad loved every minute of it. He recalled: "My favorite activity during those trips was leaning (from the back seat) against the front seat just to the right of my dad's head, chattering my endless questions into his ear, monitoring the odometer, and watching oncoming trucks and cars with wide eyes while we whizzed past other cars on the narrow two-lane highways of the day". Safety was a different concept entirely: "Remember, seat belts and other safety features did not exist then, at least not in aging passenger cars. So kids were free to move about the cabin, and often did".

Great-Grandpa Clifford had his own way of making the miles pass. "Dad loved to tell what he called stories, tall tales that were fun to hear and often ridiculous enough to be believed," Dad recalled. Among the greatest hits were "mosquito stories from the Philippines" featuring two giant mosquitoes perching on the foot of Dad's bunk, debating: "'Shall we eat him here or carry him down to the swamp to eat him?' 'We should eat him here: if we carry him down to the swamp, the big mosquitoes will get him!'". There were also "the famous Yuma sand dunes canal building story/biscuit anecdotes, many 'When I was a little girl' tales, [and] the perennial 'I had to kiss my elbow to turn into a boy' yarn".

Road construction was constant, and detours were frequent. Dad remembered that "getting lost on those detours was common" and Great-Grandpa Clifford "always said that they set them up so that you would lose your way and have to patronize some of the local stores, restaurants, motels and gas stations". Through it all, Great-Grandpa Clifford would sing, "in his pleasant off-tune way, 'Detour, There's a Muddy Road Ahead'".

One year, probably the summer of 1948 or 1949, they stopped to see the Carlsbad Caverns. Dad had read a pamphlet about how the cave was discovered when a man "had camped by a mountainside and seen countless bats coming out of the side of a mountain". He was deeply confused, since "when Mom finally explained that they were not talking about baseball bats, things were a lot easier to understand". The experience left a lasting mark: "I still have a profound fascination with caves and other secret places," Dad reflected. "A Freudian would reasonably hypothesize that this fascination influenced my choice of careers. Of course, Freudians hypothesize lots of things".

Context for this story

Read more in Chapter 3 →